Devil on the Deep Blue Sea: The Notorious Career of Captain Samuel Hill of Boston

Bullbrier Press, 2006

Winner of the 2006 John Lyman Book Award for best Maritime Biography by the North American Society of Oceanic History

Available at Amazon.

Reviews of Sam Hill

“Mary Malloy’s SAM HILL is a tour de force -- a fascinating, highly readable, and meticulously researched portrait of an extraordinary American mariner and his age. Highly recommended.”

– Nathaniel Philbrick, best selling author of In the Heart of the Sea, Sea of Glory, and Mayflower

“meticulously researched and engagingly written”

– Seattle Times, 26 June 2007

“Seeking the true Sam Hill” by Tom Brown

More information on Sam Hill’s link to Lewis & Clark is available at: “Passing the Hats: Collections of Lewis and Clark on the Columbia River,” Discovering Lewis and Clark, 2007.

Go Inside the Book

- Who is Sam Hill?

- The rescue of John Jewitt from the captivity of Chief Maquinna at Nootka Sound

- Lewis and Clark in the Columbia River

- The Sexual Practices of Sailors, Part I: Girls at Home and Homoerotic Encounters at Sea

- Ashore at Deshima (Dejima), Nagasaki Harbor, Japan

- The Sexual Practices of Sailors, Part II: Girls Ashore in Distant Ports (Romantic Images of Polynesian "Wahines" and the Sorry Business of Prostitution)

- The American China Trade, Part I: Sea Otter Pelts on the Northwest Coast (and Russians in California)

- The American China Trade, Part II: Finding Cargoes in the Chilean Revolution

- Privateer in the War of 1812 and Prisoner in Halifax

- The Chilean Revolution and Trade Across the Pacific

- Sam Hill on the Death of the Hawaiian King Kamehameha

- Sources

Who is Sam Hill?

Introduction: Why Sam Hill?

During the course of his first command, Captain Samuel Hill received two astonishing letters. His vessel, the brig Lydia of Boston, was more than 20,000 miles from home by way of Cape Horn, cruising on the Northwest Coast of the North American continent when the letters were delivered to his ship.

"We are captives of the Indians" read the first. It was signed by John Jewitt and John Thompson, sailors from the American ship Boston. They were the only survivors of a massacre two years earlier at Nootka Sound; their Captain and twenty-five shipmates were dead.

The second letter was from Lewis and Clark. "We were sent out by the Government of the United States to explore the interior of the continent of North America, and did penetrate into the Pacific ocean," it announced.

The letter from Jewitt and Thompson was received in May 1805, and Hill had already rescued the captives and had them on board when Lewis and Clark's letter was delivered aboard the Lydia a year later in July 1806. It was Hill's third visit to the Columbia River; the previous November, unknown to either party, the Lydia and her crew had lain at anchor less than a dozen miles from where the explorers were camped at Fort Clatsop.

Samuel Hill, at twenty-eight, had already made twelve voyages in fifteen years at sea. He had been on the coasts of Africa, Asia, North and South America, to both the East and West Indies, and this would be his first of four circumnavigations of the globe. In the course of his voyages he had, by his own account, twice risen to enormous challenges and saved ships in peril when no other man, including his more senior officers, could muster the right combination of daring, bravery, and skill.

He lived in Japan for three months in 1799, the first American ever to spend any significant time on Japanese soil. He spent a year as a prisoner of war in Halifax after his privateering vessel was captured by the British during the War of 1812. In subsequent voyages Captain Hill would rescue the victims of Malayan pirates and even become involved in events of the Chilean Revolution. He was attacked by Indians and tangled with the Russians on the coast of Alaska. He entertained the great king of Hawaii, Kamehameha, on board his ship, and witnessed the changes that came after Kamehameha's death, with the arrival of the first missionaries.

Samuel Hill lived on the fringes of world-altering events in an extraordinary chain of experiences, and he documented them in several published and unpublished articles and statements. He was an articulate and persuasive writer. If one judged him by his own word alone, Hill would be one of the great maritime heroes of the early nineteenth century.

But Samuel Hill was not the only one to write about Samuel Hill. If one judged Captain Hill from the descriptions written about him by men who served under his command, he would be a villain of epic proportions. As captain of the Lydia he was a violent and unstable tyrant, subject to fits and seizures. He beat his men mercilessly, abused them with the foulest language, threatened them with abandonment, starvation, even shipwreck. He plotted against other captains, cheated his Indian trading partners, and kept a Hawaiian girl as his sex slave. A complex, sometimes tortured man, Hill underwent a religious conversion on his final voyage, but even then he could not admit the full extent of his evil doings.

In all his contradictions and complexities, Samuel Hill represented the fledgling United States in the first wave of expansion. In an age when Americans were first venturing into the Pacific and when knowledge of new regions and new people were first becoming known, Samuel Hill was in a position to effect, for good or ill, the subsequent relations between American citizens and native people around the globe, especially around the rim of the Pacific Ocean. He was not only an eye-witness to and participant in a number of the major events of his day, but he took active measures to shape the way posterity would view his role in those events by producing his own chronicle for the popular press. From those same sources images of native people were crafted that would continue to influence both savage and romantic stereotypes for the two centuries that followed.

It is one of the intriguing accidents of history that the first encounters of Americans abroad were never carefully planned diplomatic missions, but commercial voyages. The de facto ambassadors were men like Samuel Hill. And the shipboard community, made up of young men isolated for months or years from the larger society of home and women, represented America. Sailors were the link through which the old world had encountered the new, Europeans and Americans entered the Pacific, and biota and technology were globally transported.

A half century before there was any notion of "Manifest Destiny" or organized westward expansion, before the Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark, or the Oregon Trail, American ships swarmed into the Pacific Ocean, seeking profitable products for the China Trade. The first and finest commodities were sea otter pelts, acquired along the Northwest Coast, and the legacy of the voyages that procured them reached across the continent during the period when Americans were first beginning to look westward.

Captain Samuel Hill embodied the two faces of America on the eve of expansion: at home he appeared civilized and sensible, but as he sailed into the Pacific Ocean the mask slipped away to reveal the recklessness, ambition, and violence that propelled the United States from coast to coast and around the world.

- top -

The rescue of John Jewitt from the captivity of Chief Maquinna at Nootka Sound

Chapter I: Lydia, 1804-1807: DEVIL ON THE DEEP BLUE SEA

(In which Samuel Hill proves disappointing as a hero, though he rescues Jewitt and almost meets Lewis and Clark.)

John Jewitt and John Thompson found out soon enough, when the first raptures of being rescued had faded, that they were on what sailors referred to as a "hell ship." The Lydia had a dysfunctional chain of command. The men were always poised and ready to mutiny. The original first mate and supercargo had already been dismissed and put off the ship for challenging the authority of the captain. Three different men served as chief mate in the course of the voyage, each more brutal than his predecessor. A young Hawaiian woman lived in the captain's cabin as his sexual hostage, and the captain himself behaved like a madman. This was the situation into which the Boston survivors escaped.

- top -

Lewis and Clark in the Columbia River

Figure 2: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 99-12-10/53080.

Figure 3: American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, Codx j48.

Figure 4: American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, Codx I 144.

Figure 5: Museo de America, Madrid, CE00367.

- top -

The Sexual Practices of Sailors, Part I: Girls at Home and Homoerotic Encounters on Shipboard

When he was eighteen Sam Hill sailed from Boston for Indonesia and back, in a voyage that lasted almost a year and a half under the command of Captain Robert Haswell. He described the voyage in a single enigmatic paragraph in his autobiography.

In the Autumn of 1795 I entered as an Ordinary Seaman on board the Ship John Jay of Boston under the Command of Robert Haswell Esquire, we proceeded to Battavia in the Island of Java, where we loaded a Cargo & returned to Boston in Jany 1797. While in Battavia it pleased Capt Haswell to permit me to live on shore with him at the Company’s Hotel, & where he allowed me to use his Coach, to Ride in the Country or elsewhere, whenever I pleased provided I returned before Eight O’Clock in the morning or more properly from day light until Eight in the morning and as Capt. H. required but a few hours of my time each day I had much leisure, by which means I acquired some knowledge of the Malayan Language, as spoken at Battavia, & also a very considerable addition to the Stock I already possessed of a knowledge in the ways of Iniquity.

There can be no doubt but that the iniquitous ways that young Sam Hill came to know so well were principally sexual in nature, and Robert Haswell is an interesting potential co-conspirator in the degradation of the younger sailor’s morals. The captain’s sister, Susanna Haswell Rowson, was then the best selling author in America. Her book, Charlotte Temple: A Tale of Truth, described in vivid and horrifying detail what happened to a nice young woman if she had sex without being married.

The gulf between the desires and expectations of a young sailor, and the rigid and rigorously-patrolled acceptable behavior of a young woman of his own background, was more difficult to navigate than the widest part of the Pacific Ocean. In the age of sail, many boys and young men went to sea just at that point in their emotional and social development when they would ordinarily begin to seek out female companionship and explore romantic and sexual relationships. Had they stayed home, their own society would have provided them with a framework for meeting suitable young women. Within the context of family, church, and community, potential partners could be brought forward for flirting, courtship and marriage.

On shipboard there were no options for meeting marriageable young women, and sailors like Sam Hill were robbed by circumstance of normal socializing experiences for the whole period of their pubescent and adolescent development. The picture they got of girls from books like Rowson’s (which must certainly have been in the possession of her brother, and consequently available on the John Jay) did not allow for any kind of relationship to be considered that did not start with the expectation of a direct and rapid road to the altar. And though marriage was clearly the only road acceptable road to sexual relations, it also served social functions that could make it seem less than desirable, for both women and men.

The father of the heroine in Rowson’s story considered his sisters to have been “legally prostituted to old, decrepit men,” by marriages that were arranged principally to provide them with social position. Young love would seemingly have made for a more perfect union, but if love did not lead directly to marriage the girl was in a far worse position, because in passion she might forfeit, as Charlotte Temple did, “the only gem that could render [her] respectable in the eye of the world.” Rowson ranted quite vigorously about this.

Gracious heaven! when I think on the miseries that must rend the heart of a doating parent, when he sees the darling of his age at first seduced from his protection, and afterwards abandoned, by the very wretch whose promises of love decoyed her from the paternal roof ... her bosom torn between remorse for her crime and love for her vile betrayer ... my bosom glows with honest indignation, and I wish for power to extirpate those monsters of seduction from the earth.

Oh my dear girls—for to such only am I writing—listen not to the voice of love, unless sanctioned by paternal approbation: be assured, it is now past the days of romance.

Rowson believed that there was a “natural sense of propriety inherent in the female bosom.” Men did not share it. Even a good man might be unable to resist his nature, and the results could then be disastrous. Once a girl had “surrendered” herself to a man—even a good man, and even under pressures which might as easily be interpreted as rape as “seduction”—she could no longer expect his respect. She had, in effect, made herself unmarriagable. Rowson documented this in the scene where her heroine, Charlotte Temple, is abducted from her English school to be taken on shipboard and thence to America.

“I cannot go,” said she: “cease, dear Montraville, to persuade. I must not: religion, duty, forbid.”

“Cruel Charlotte,” said he, “if you disappoint my ardent hopes, by all that is sacred, this hand shall put a period to my existence. I cannot—will not live without you.”

“Alas! my torn heart!” said Charlotte, “how shall I act?”

“Let me direct you,” said Montraville, lifting her into the chaise.

“Oh! my dear forsaken parents!” cried Charlotte.

The chaise drove off. She shrieked, and fainted into the arms of her betrayer.

Though Montraville has clearly kidnapped Charlotte, and will subsequently “seduce” her on shipboard, she is ultimately rejected by him as unworthy because she submitted. The pre-marital sexual encounter became “misfortune worse than death.” Charlotte knew this would happen of course. “Never did any human being wish for death with greater fervency or with juster cause” than she, unmarried, pregnant, and abandoned in New York City.

The other couple that ran away with Charlotte and Montraville consisted of a loose and hardened woman from the heroine’s school and another soldier from Montraville’s regiment. The woman’s outrageous behavior and lack of morals is easily understandable: she is French. The evil of the man’s behavior is more complex. He expects that once Charlotte’s lover and virginity are both gone, she will be willing to have sexual intercourse with him without any discussion of either love or marriage. She has now, in his eyes, become that kind of woman. In the sequel to Charlotte Temple, in which we learn the story of Charlotte’s love-child Lucy, Susanna Rowson, explains that “men who in early life have associated with profligate women form their opinion of the sex in general from that early knowledge.” It is, consequently, the fault of women that some men treat all of them badly.

There were other books that Samuel Hill was reading at this point in his life that had a very different message. “I had accidentally fallen in with some immoral Books previous to my going to Sea,” he wrote, “& those parts which most easily caught my attention were Profane & Lascivious Allusions, & quaint expressions of Ridicule.” Among the books that he “perused with much delight” were the novels of Laurence Stern.

Unlike the fevered Charlotte Temple, the heroes of Sterne’s novels Tristram Shandy and A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy were casually, even hilariously sexual. Handsome matrons and lovely chambermaids fell against them by accident, hands strayed, and before they knew it, Sterne’s heroes were “winding the clocks” of females thrown unexpectedly into their paths. There were never any consequences from these liaisons, no expectations of marriage, no fear of pregnancy, the men simply moved on to the next encounter.

- top -

Ashore at Deshima (Dejima), Nagasaki Harbor, Japan

Figure 7: Peabody Essex Museum, M13,393

Sam Hill signed aboard the voyage as a seaman that fall, and the ship proceeded around the Cape of Good Hope to the Dutch East Indies. The capital of the Dutch colony was Batavia (now called Djakarta), a thriving town on the northwest end of the long island of Java, and it was to that port that the Franklin made it’s way, arriving in April 1799. For Hill, it must have been a pleasant return to the place where he had, three years earlier, added so considerably to his “knowledge in the ways of iniquity.”

When Devereux and Burling went ashore to negotiate with the Dutch agents for the East India Company, they were made an unexpected offer. The Dutch had an exclusive monopoly on the European trade to Japan, but they didn’t have a ship to send on their annual voyage. If the Franklin would make the voyage, the Americans would be paid thirty thousand piasters to carry a freight to Japan and another back to Batavia The payment would be made in coffee, sugar, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, nutmegs, and indigo, in any combination. The outlines of the voyage were narrowly defined: the Dutch ships always left Batavia in mid-June to follow the seasonal monsoon winds, and they always left Japan near the first of December when the monsoon predictably reversed direction. The ship would be paid even if it were unable to enter Japan, unable to get a cargo once there, or even if it were wrecked along the way. The value of the silver piaster was not far off from that of the Spanish dollars they carried, so the ten-month round-trip to Japan would double the Franklin’s buying power in Batavia. It was, simply, an irresistible offer.

The Franklin would not be the first American ship to enter the waters of what Herman Melville called “that double-bolted land, Japan.” Two American vessels, the Lady Washington and the Grace, had attempted a landfall in Japan in 1791, but were repelled by the locals, and the American-flagged Eliza had made the previous voyage for the Dutch, but was presently missing and presumed lost. For all other ships from the United States and Europe, Japan forbade entry.

The VOC managers in Batavia gave Captain Devereux charts and instructions for the voyage to Japan, a Dutch flag to fly in place of the stars and stripes, and a young Dutchman named Hendrik Doeff, to manage the company’s business on shipboard and to communicate with the company’s employees who were resident in Nagasaki. The Franklin sailed from Batavia on 17 June 1799, with seventeen men on board, including Doeff and his Javanese servant. [When] Hendrik Doeff went ashore to take up his residence in the Dutch compound and Samuel Hill went with him. For Hill, this was an extraordinary opportunity. All the previous American visitors had lived aboard their ships when they came into Japanese waters; he was the first to live ashore in Japan.

The place in which he found himself, Deshima, was a fan-shaped island in Nagasaki harbor constructed for the Portuguese 165 years earlier. (Tradition says that when the workers building the island asked the shogun what sort of place he wanted them to construct, his response was to spread his fan and lay it before them.)

Figure 8: Nagasaki University Library, Economic Brach, Library Muto Collection

Figure 9: National Museum of Ethnology, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2821-1

Figures 10, 11, 12, 13: Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture

Note on the spelling of “Deshima”: The orthography of Japanese names in English is not entirely consistent, and the spelling “Dejima” is currently preferred by the Dejima Restoration Office at the Nagasaki City Board of Education. As I have relied so heavily on Dutch and American sources, however, I have chosen to use the spelling found more commonly in those materials.

- top -

The Sexual Practices of Sailors, Part II: Girls Ashore in Distant Ports

(Romantic Images of Polynesian “Wahines” and the Sorry Business of Prostitution)

Chapter IV: Helen, Adventure, Mary, Indus, 1800-1809: ACQUIRING THE ACCEPTABLE ACCOUTERMENTS OF ADULTHOOD

(Sam Hill gets a wife, a house, a child, and makes six more voyages)

In all the places that he had been prior to the Lydia’s voyage, Hill’s shore visits were very likely focused on consorting with professional prostitutes. Though that term implies that such girls or women made a choice in their profession, it was an industry that few, if any, of them entered into willingly, though sailors liked to think that they had. Coerced by poverty, family circumstances, or brute force into a life in the sex business, these women were, nonetheless, available for sexual intercourse with sailors on a commercial basis that had a well-understood meaning in both the culture of the port and the culture of the ship. Girls who lived in the towns, villages, and rural areas beyond the port districts were generally not available for casual sexual contact. Relationships that might lead to pregnancy were carefully controlled within the social and cultural context in which those females lived.

Once he rounded Cape Horn on the Lydia, Sam Hill found that everything had changed. In the Polynesian Islands of Tahiti, the Marquesas, and Hawaii, Hill’s sailor predecessors had found sexual partners on an entirely different, seemingly casual, even “innocent” basis. Hill must have been thinking about this during the six and a half months that it took to make the voyage from Boston to Hawaii, because almost immediately upon his arrival there on 5 March 1805, he invited a Hawaiian girl of about fifteen years of age to come onto the ship for sex, and then sailed away with her across the Pacific.

The sexuality of Polynesian women had been described since the very first encounters by British mariners. Captain James Cook and the men who served on his ships discussed it candidly in their published narratives and Sam Hill wrote of having read “Cook’s Voyages” while still at school in Machias.

American sailors consequently arrived at the islands of Polynesia with heads bursting with notions of willing wahines. After months on the ship where sex was a topic to think about and talk about, few young men attempted to restrain themselves when let loose on a tropical island. The problems of “ruining” a girl by using her to satisfy sexual urges without commitment did not exist on these islands, or so foreign sailors were eager to believe. Discussion of such a serious topic was impossible anyway, the only common languages were sex and trade goods.

The perception that there were no social standards governing sexual intercourse among Polynesians was widespread among American and European sailors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Whether this was true or not has been debated by Polynesian people, anthropologists, and historians ever since. There certainly were rigorous social standards regarding other behavior for women, including taboos against riding in canoes and sharing meals with men (both of which were observed and discussed by outsiders). That sexual intercourse should not receive the same parental disapproval as riding in a canoe dumfounded American sailors, who did not make much effort to understand the difference, though they willingly took advantage of it.

Anthropologist Marshall Sahlins argues persuasively that the Hawaiians mistook Captain Cook for their God Lono, because his appearance coincidently coincided with the most important elements of the myth cycle. By extension, if the visiting British sailors were Gods, then children fathered by them would inherit powerful mana, and Hawaiian women were consequently eager, even urged, to have intercourse with foreigners. Even if this supposition were true, however, the Hawaiians would certainly have begun to have serious doubts about the celestial nature of British and American sailors after a dozen or so ships had come into the islands, and yet the frequency of sexual relations did not diminish.

Historian Greg Dening says that for the Marquesans, sexual behavior was defined by a cultural code, outsiders simply didn’t recognize it, though most sailors did recognize differences in rank among Polynesians, and knew that higher ranking women were not available to them. In the Marquesas, the most readily available girls lived outside of the taboo culture, either temporarily, because they were going through a period of socialization that included sexual games and experimentation, or permanently, by virtue of their lack of rank, in which case a relationship with a foreigner might increase their status. In addition to being available, these women were also extraordinarily attractive to the eyes of European and American men. Ebenezer Dorr, who made a voyage to the Northwest Coast aboard the Boston brigantine Hope, wrote about a stop that his ship made in the Marquesas Islands in 1791 as they sailed north in the Pacific.

A note on Sahlins and Dening: Marshall Sahlins’ interpretation of the sexual behavior of Polynesians in Islands of History, has been widely mis-stated in the years since it was first published. The notion that “white” men were perceived as gods, and therefore desirable sperm donors for the progeny of Hawaiian women, is the simplistic way I have heard Sahlins’ theory described by otherwise thoughtful and knowledgeable historical interpreters in Hawaii. The sudden and unexpected appearance of alien people on their islands certainly caused some confusion among the Hawaiians about who the strangers were and where they originated. But a supernatural origin was an explanation that could not be sustained over time, and in later descriptions of sexual encounters with Hawaiian, Tahitian, and Marquesan women, the encounter had clearly become as much a commercial transaction as anything else, often with the young women the exploited victims of male relatives and foreign sailors.

Greg Dening’s description of Marquesan society and sexual practices appears in his book Islands and Beaches: Discourse on a Silent Land, Marquesas 1774-1880 (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1980).

- top -

The American China Trade, Part I: Sea Otter Pelts on the Northwest Coast (and Russians in California)

Chapter V Otter, 1809-1812: “Evil, Ill-minded, Mischiefmaking Persons”

(Considering the Lamentable Fate of Robert Kemp, et. al.)

By 1810 it was clear to everyone involved in the trade that sea otters on the Northwest Coast were destined for extinction. Some American captains had begun looking elsewhere for them, and the place they were found in abundance was the coast of California. Unlike whaling and sealing, where American crews did the hunting and preparation of the prey, the sea otter pelt trade had always relied on Native hunters on the Northwest Coast. California Indians did not have the same hunting or ocean-going traditions, and so American captains began to engage Northwest Coast Indians or Aleuts and take them to California for the hunt. These hunters were transported south, with their native canoes or kayaks, on the decks of the American ships.

Aleuts lived within the boundaries of territory claimed by the Russians in Alaska, and consequently merchants from the Russian-American Company became the partners of American captains in these ventures. The first of these voyages took place while Samuel Hill was on the Northwest Coast commanding the Lydia. By the time he returned on the Otter, they had become routine. Captain Blanchard of the Katherine decided to try his luck at one of these ventures, and headed north to Sitka, the Russian capital of Alaska. There he contracted with Aleksandr Baranov, the Governor of the Russian-American Company, to take a crew of Aleut and Kodiac hunters, with 50 kayaks or baidarkas, and hunt on the coast of California.

This trade was strictly illegal. California had been claimed by Spain for two hundred years before the Americans first arrived there, and ordinarily captains from the United States were instructed by the owners of their ships to respect Spanish sovereignty in California. But the Spanish had only a very limited sea otter hunt going on that coast, with furs bound for Manilla rather than Canton. With the animals becoming more and more scarce on the Northwest Coast, the siren call of California was irresistible to both the Americans and the Russians.

The Russians would have preferred to run the California business without American assistance, but they were always short on ships. They contracted them when possible, but preferred to buy them if the captain were willing to arrange the sale, and they usually paid for them in pelts. One of the first American vessels sold to the Russians was the Juno of Bristol, Rhode Island, and it was a ship well known to Sam Hill from his previous voyage on the Northwest Coast. Captain John DeWolfe had, according to Hill, spoiled much of his trade by giving exorbitant prices for furs, as he dumped his remaining cargo before selling his ship.

On the 24th of May, 1810, the familiar outline of the Juno hove into view as the Otter crossed Clarence’s Straits. Now, of course, the captain was a Russian, Christopher Martinevich Benzemann. The Juno travelled in company with a Boston ship, the O’Cain, which was transporting Aleut hunters to California under contract to the Russian American Company.

- top -

Privateer in the War of 1812 and Prisoner in Halifax

Chapter VI Ulysses, 1813-1814: PRIVATEER AND PRISONER

(Being an Account of How Sam Hill Spent the War of 1812)

Samuel Hill had certainly known that war was a possibility when he left Canton, but he had not received any additional news since he came around the Cape of Good Hope. His seafaring prospects were now limited, as commercial voyages would be severely curtailed and he was disinclined for service in the Navy. He decided to live at home for a while with Elizabeth and their two sons, seven-year-old Frederic and four-year-old Charles.

Their home on Myrtle Street was on what is commonly called the “backside” of Boston’s Beacon Hill. At that time it ran down to an active waterfront, which has long since been filled. The neighborhood was slightly less transient than the North End where Sam and Elizabeth had lived when they were first married. Though there were still numerous mariners living in boarding houses, families, many of them African American, were beginning to put down roots.

There were few options during the War of 1812 for mariners who wanted to avoid the conflict, and eventually it became clear to Hill that if he was to work at all during the period of the war, he would have to engage in the risky business of carrying a cargo through seas that were patrolled by the British Navy. Ten months at home was enough for him, however, and on 9 April 1813 he left Boston again, as captain of the brig Ulysses. “I was induced,” he wrote, “though contrary to my own Judgement, to undertake a Voyage to France.” This was not a last minute decision and Hill must have been planning his departure for several months. He owned the Ulysses in partnership with Oliver Keating, for whom he had worked on the Otter enterprise.

The Ulysses was a new vessel and carried a substantial armament for its size. The cannons were both for protection and to provide Hill with the option to attack English ships if they looked vulnerable enough to be taken. Permission to attack the enemy was provided in a special Congressional license called a “letter of marque,” which gave its name to the vessel’s mission as well. (Sam Hill referred to the Ulysses as a “Letter of Marque Brig.”)

During the American Revolution, without a navy, a treasury, or even a currency, the Continental Congress had depended upon private ships to engage in battles with British naval and commercial vessels. The benefit for the owners and crews was that captured ships and cargoes could be kept as prizes. The benefits were substantial for the government as well. In in addition to the obvious harassment of enemy ships, the government received a percentage of the prizes, while the private owners bore all of the costs of the vessel, its outfit, and its crew. Privateering undermined commercial voyages that supplied the opposition’s war effort, and removed men from available service in the enemy’s naval and merchant fleets.

During the War of 1812, privateers and letters of marque were once again an important component of the United States’ overall naval strategy. There were twenty-three ships in the U.S. Navy, which performed famously during the war in ship-to-ship engagements, but which were no match numerically for the British. More than five hundred privateers and letters of marque added substantially to the potential for an American naval presence, especially in the harassment and capture of British merchant ships. While the U.S. Navy captured 254 vessels, the number captured by private venturers was 1300. Without privateering, American commerce would have ground to a halt for the whole period of the war, as the movement of goods along the coast and to and from foreign destinations could not have been protected by the efforts of the Navy alone.

Thomas Jefferson wrote about the role of privateers and letters of mark on the Fourth of July, 1812. “What is a war?” he asked. “It is simply a contest between nations of trying which can do the other most harm.” By the time he wrote this, as many as seven thousand American sailors had been pressed into the British Navy, and more than nine hundred vessels had been taken.

What difference to the sufferer is it that his property is taken by a national or private armed vessel? Did our merchants, who have lost 917 vessels by British capture, feel any gratification that the most of them were taken by His Majesty’s men of war? ... One man fights for wages paid him by the government, or a patriotic zeal for the defence of his country, another, duly authorized, and giving the proper pledges for his good conduct, undertakes to pay himself at the expense of the foe, and serve his country as effectively as the former. In the United States every possible encouragement should be given to privateering in time of war with a commercial nation. ... By licensing private armed vessels, the whole moral force of the nation is truly brought to bear on the foe, and while the contest lasts, that it may have the speedier termination, let every individual contribute his mite, in the best way he can to distress and harass the enemy, and compel him to peace.

The British took the threat of privateers very seriously. They knew that their maritime commerce could be devastated by private adventurers. A month before Jefferson made his statements about privateering The London Statesman published an article on the subject, which reminded British readers of the success of privateers during the American Revolution, when the country “was in her infancy, without ships, without seamen, without money,” and at a time when the Royal Navy “was not much less in strength than at present.” Scan 174-175

The American China Trade, Part II: Finding Cargoes in the Chilean Revolution

Chapter VII Ophelia, 1815-1817: OF SILKS AND SHIPS AND WHALES TEETH...

(An unsuccessful voyage, which nevertheless proves interesting because of a Revolution in Chile)

By May 1815, Thomas Perkins and William Sturgis had probably been considering a venture to Chile for several years. Closed to foreign trade by the Spanish colonial government, the ports of Chile had been declared open in 1811 by the junta that took control of the country in a revolution against the Spanish crown. The War of 1812 had prevented the Boston merchants from exploring the trade fully, and new information that was becoming available in 1814 and 1815 made the prospects for success in Chile seem very realistic.

Captain David Porter, who had commanded the U.S. frigate Essex in the Pacific Ocean during the War of 1812, had returned to New York the previous summer, filled with enthusiasm for Chile and promoting the prospects for trade there now that the Spanish had been ousted. Among several revolutionary factions, Porter had thrown his support behind José Miguel Carrera, a charismatic and handsome young man who had been the second in a series of revolutionary leaders to seize control of Chile. In their fight for independence, Porter wrote, Chileans “looked up to the United States for example and protection,” and he believed that they should be supported.

Americans supported Chilean independence, emotionally, philosophically, and, to a certain extent, financially. Not only did Americans sympathize with their brothers and sisters in the hemisphere who wanted to throw off the yoke of European control, but the Spanish had always prohibited free trade in their ports. With independence came tantalizing opportunities for merchants like Perkins and Sturgis to tap the resources of South America.

Hill did not have high expectations for success in Hawaii though he was, for the first time on this voyage, in familiar trading territory. On March 30th, he learned from islanders at Waikiki that the Hawaiian king, Kamehameha (or Tamahahmaha, as Hill wrote it), had moved his court from Oahu to a village near Kealakekua Bay on the big island of Hawaii. This was a location well known to Americans and Europeans as the place where Captain James Cook had been killed in 1779. The Ophelia proceeded there and arrived four days later.

Hill had spent significant time in the Hawaiian Islands on the voyages of the Lydia and Otter. The king, wrote Hill, “immediately recognized me and seemed glad to see me.” In the course of the day Hill introduced his business. Would the king provide him with a cargo of sandalwood in exchange for Spanish Dollars? Kamehameha was doubtful. He had none cut, he explained, and his people were unwilling to go to the mountains to cut it because they had not been paid by the last two Boston captains who had come through the previous year.

Besides, what Kamehameha wanted was not dollars but ships. He had already purchased three from Americans, the Albatross, Lydia, and Cleopatra’s Barge, and he had had a small schooner built for him by Americans in 1805, which he named Tamana after his Queen. He used it to upgrade to a larger vessel, the Lelia Byrd, which was purchased with the Tamana and a cargo of sandalwood.

Kamehameha’s current dispute with two Boston captains, William Heath Davis and Jonathan Winship, Jr., was over the Lelia Byrd. Davis and Winship had sold theirvessels, the Isabella and the O’Cain, to the Russians at Sitka in 1814, and had then taken passage on the Salem ship Packet to Hawaii, where they negotiated a deal with Kamehameha for a cargo of sandalwood. Having no ship of their own on which to transport it, they had “borrowed” the Lelia Byrd, and Kamehameha wanted it back.

- top -

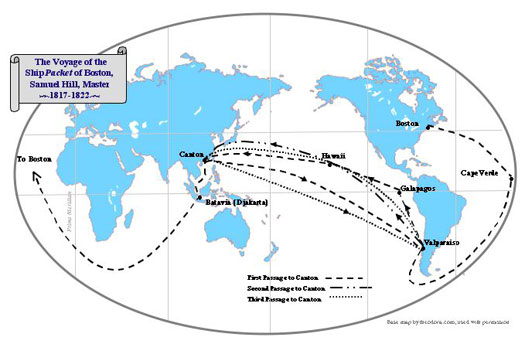

The Chilean Revolution and Trade Across the Pacific

Chapter VIII Packet, 1817-1822: OF HANDKERCHIEFS AND REVOLUTIONARIES

(A voyage, the success of which would be debated for years, which includes another Revolution in Chile, the Death of the King of Hawaii, and Sam Hill’s thoughts on Religion.)

Having been gone from home three months shy of two years, Sam Hill did not spend much time with his wife before planning his next venture. After a month in Boston he was already approaching the Ophelia’s owners with a new plan for the Chilean trade.

Behind him in Chile, the situation was rapidly changing. He must have almost crossed paths with José Carrera who, having been to New York seeking support for his cause, sailed south in December 1816 and arrived at Buenos Aires even as the Ophelia was sailing into Boston harbor. Almost simultaneously, Bernardo O’Higgins was returning from Argentina to Chile with José de San Martín, to lead a decisive charge against the Spanish at Chacabuco and bring the revolutionary government back into power. Hill would return to Chile in time to witness the rest of the major events of the revolution that would bring Chile, once and for all, into the community of independent nations.

A welcome sight greeted him as he dropped anchor in Valparaiso in October 1817. As the “breeze freshened from the S.W., the Patriot flag was plainly perceived to be flying on the Forts on Shore.” Chile was once again in the hands of the independence-minded revolutionaries. An armed brig approached on behalf of the new government, it was the Eagle, purchased from her American owners, and still commanded by her American captain, patrolling the coast looking for Spanish cruisers.

What began as a very promising stay in Santiago was, however, doomed by the political struggle unfolding around him. By early December word began to circulate that Don Mariano Ossorio, who had been the President of Chile on Hill’s last visit and was now General of the Royalist forces, had already left Lima with an army to invade Chile. “It was suspected,” Hill wrote, that “their orders was to attack the Port of Valipo by Sea and land.” In charge of the revolutionary or “Patriot” forces, as Hill and other Americans called them, were Generals José de San Martín and Bernardo O’Higgins. San Martín was marshalling his forces even as Hill first travelled from Valparaiso to Santiago.

Unlike the vast body of the Chilean population, whose behavior in the current situation was viewed with contempt by Hill, San Martín and his troops stood out as admirable. “Amidst all this Vacillating Conduct of the Inhabitants Generally the Soldiery remained firmly attached to the cause of Liberty, or what they believed liberty to be,” he observed. Much of the credit went to San Martín, who trained them with “rigorous discipline.” They followed his personal example and “patiently submitted to hunger & fatigue in long & rapid marches under a burning atmosphere.” On them, Hill concluded, rested the hope for a free and independent Chile.

- top -

Sam Hill on the Death of the Hawaiian King Kamehameha

On the eleventh of March, 1820, Hill arrived once again in Hawaii, exactly fifteen years after his first visit there on the Lydia. He had been there many times since and had both observed and contributed to enormous changes in the local culture, economy and environment. He would visit Hawaii one more time before the Packet returned to Boston, and on these two visits would note two events the impact of which would resonate over the next two centuries. He was about to learn of the death of King Kamehameha I and the breakdown of the traditional system of kapu or “taboo”; on his next stopover he would meet the first American missionary.

The news of the king’s death was brought instantly to the ship upon its arrival at Maui, and was written directly into Hill’s log.

The former King of these Islands Tamahamahah died about 10 months Since and after some Slight Quarrels in which Teremyty (the former Kings Brother) and a few of his adherents were Killed, the Son of the late King, Rihu Rihu was proclaimed & supported unanimously as King of the Sandwich Isles.

Hill had known the old king for many years and had spent some considerable time with the new king when he visited aboard the Ophelia four years earlier. While the former was acknowledged to have been a canny leader, the latter had not impressed Hill very favorably. At that time Hill had predicted that when Liholiho succeeded his father there would be “many Irregularities Committed,” but he did not expect the nature of the change he saw.

Sources:

An extraordinary wealth of material describes Hill’s interlocking ventures, including two manuscript journals of the Lydia voyage, three of the Otter, and one each of the Franklin, Ophelia, and Packet, as well as logbooks or journals from several of the ships met along the way. Hill was described by the Chinook Indians to Lewis and Clark, and he appears both in the explorers’ journals and on one of their charts—where they named a bay after him. There are also court records from Hill’s two lawsuits. Among writings that survive from Samuel Hill himself are two newspaper articles, his epic letters to the owners of the Ophelia and to John Cushing, and an unpublished manuscript that includes his own detailed logbooks kept aboard the Ophelia and Packet, and an “Autobiography” written aboard the Packet after his evangelical experience inspired by the Anglican missionary in China, Robert Morrison. More detailed sources of each chapter are given in the book.

- top -